Introduction

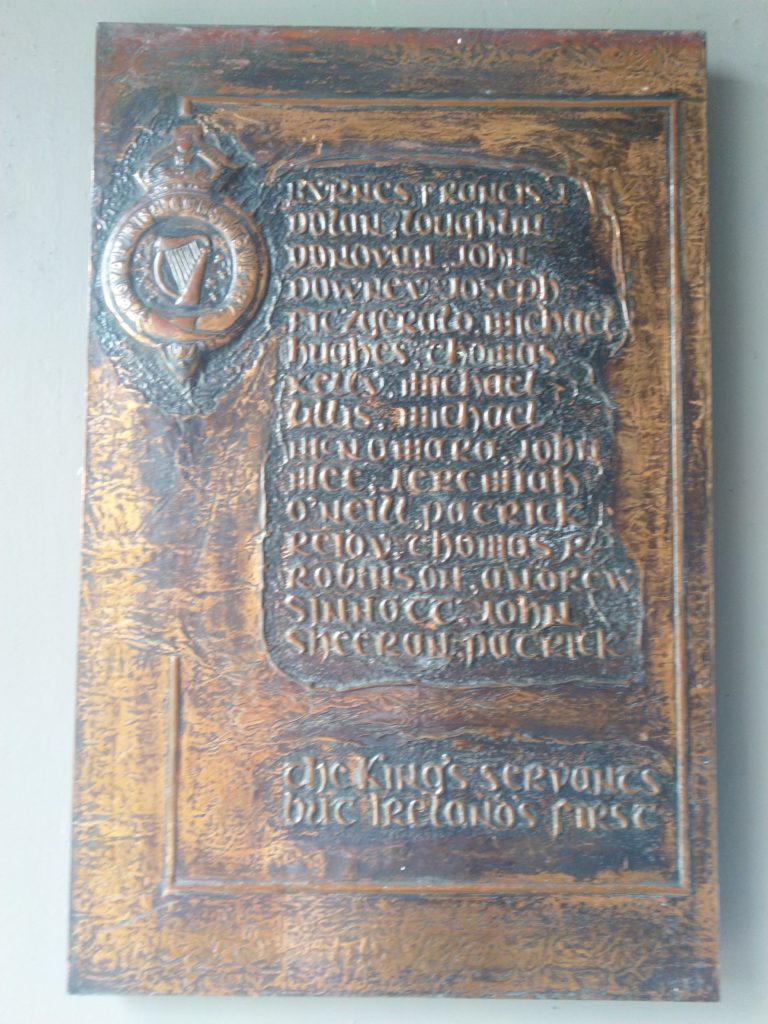

On June 19th 1920, fourteen rank and file members of the Royal Irish Constabulary in Listowel defied the order of their superior officers and refused to hand over the control of the barracks to the British Military, and to adopt a shoot to kill policy against the local community. This incident – forever more known as the Listowel Police Mutiny – was a seminal event in the Irish War of Independence.

But what led to the incident and what were its long term repercussions?

To mark the centenary of this significant historic event, Kerry Writers’ Museum presents this commemorative exhibition. It features recounts of events by leading historians, first-hand accounts from those involved, photographs, and video recordings of family members of the Listowel ‘mutineers’.

To view film recording of Rev. Fr. J. Anthony Gaughan on the Listowel Mutiny watch below

Lead Up to the Mutiny

The Listowel RIC Mutiny had all the ingredients of high drama. It was triggered off by the visit of ex-war hero, Colonel Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth, Divisional Police Commissioner for Munster. However, the situation had been building up for some days.

On the night of 16th June 1920, RIC constables in Listowel received orders to hand over their barracks to the British military effective at noon the next day. They also received orders that they were nearly all re-assigned to other stations in Kerry to act as scouts for the military. Three sergeants and one constable were to stay in Listowel as scouts. None of the men were from the area, because the RIC always stationed men away from whence they came; but these men had acquired valuable local knowledge from their duties and experience in the area.

The constables held a meeting and decided unanimously not to obey these orders. They saw that they were going to be used in a war against their own people. They reasoned that whatever the outcome, the British soldiers could go home; but the constables would have to live in Ireland with the consequences of their actions. They even considered the possibility that they may have to resist by force. They figured there were enough bombs, rifles, and revolvers there to hold out at least a few days.

They telephoned the County Inspector in Tralee at 9pm and told him they were refusing to leave their barracks. There was no immediate response, but District Inspector Thomas Flanagan later got orders by phone from County Inspector Poer O’Shea to have the constables assemble at 10am the next day.

County Inspector O’Shea arrived at 10am on the 17th to address the men. He chastised them and advised them about the seriousness of their refusal to obey these orders. He told them the military were required to be installed in the barracks at noon and that this applied to all headquarters in the Province of Munster. O’Shea demanded: “Do you refuse to obey the order of the Divisional Commissioner, an order that applies to all Munster, and bring discredit on the Police force?”

Thirty-one year old Constable Jeremiah Mee from Glenamaddy, Co. Galway; whom the constables had chosen as their spokesman, affirmed his refusal. O’Shea advised him that he should resign. Mee offered his resignation immediately. O’Shea asked if anyone else was prepared to resign. Thirteen other constables each stated “I resign” in turn.

Stunned and caught off-guard by their resignations, Inspector O’Shea softened his stance and asked them to write down their concerns which he would relay to his superiors and then he left. Meanwhile, noon came and went without any sign of the planned military takeover. The constables remained in the barracks anxiously and heard nothing further until the next night. At 10pm on the night of the 18th, the constables received a phone message from the County Inspector to the District Inspector. They were ordered to assemble at 10am the next day with side arms, belt and sword to be addressed by Colonel Smyth; with whom none of them were familiar.

Lieutenant-Colonel Gerald Bryce Ferguson Smyth had been named as Divisional Police Commander for the Province Of Munster on 3 June. This appointment came directly from the British Cabinet, who also put him in charge of the military for the Province of Munster. He came from a staunch Unionist family and had lost his left arm at Le Cateau, France in August 1914. He and several police and military officials had apparently planned a tour of the main stations in Kerry.

The Listowel Mutiny

Next morning, June 19th, Colonel Smyth arrived at Listowel barracks. He was accompanied by the British Government appointed Police Advisor to the Dublin Castle administration Major General Henry Hugh Tudor, Major Letham, the O.C. of the military stationed at Ballinruddery, Captain Chadwick, and Assistant County Inspector Dobbyn. Smyth addressed the constables in the course of relaying the new Order No. 5, issued on 17th June. It empowered the police to shoot IRA suspects (which was left broad enough to include anyone) who failed to surrender when ordered to do so. When Smyth began to speak, Mee stepped out, saluted him, and told him that the constables understood that this was to be a meeting with police authorities, and that they objected to the presence of military officers.

According to Mee, Smyth simply ignored him and proceeded to make the following speech:

Hear an audio re-enactment of Col. Smyth’s speech by actor Muiris Crowley here

After a few tense moments, Smyth approached the constable at the top of the line; an Englishman named Chuter and demanded: “Are you prepared to co-operate with me?“ Chuter, along with each man Smyth approached referred him to Mee, their spokesman who responded indignantly:

“By your accent I take it you are an Englishman and in your ignorance forget that you are addressing Irishmen.” At this point, Smyth then corrected Mee; informing him that he came from Banbridge, Co. Down. Mee nevertheless responded: “I am an Irishman and very proud of it.” Having lost his temper, Mee removed his cap, saying “This too is English; you may have it as a present from me.” Removing his belt and bayonet, he added: “These too are English and you may have them. To Hell with you. You are a murderer!”

To view Jeremiah Mee’s response to Colonel Smyth recorded by his daughter Teresa Mee – watch below

Col. Smyth ordered District Inspector Flanagan “Place that man under arrest.” Flanagan and Head Constable Plover escorted Mee to the kitchen. Five minutes later, all the other constables rushed in, prompted by Constable Thomas Hughes from Hollymount, Co. Mayo; and pulled Mee away with them to the day room where they had previously assembled.

Flanagan and Plover went into the District Inspector’s office, where the officers had convened, behind a closed door. After a few minutes, Flanagan whom the men respected; came and told the men that Major General Sir Henry Hugh Tudor wanted to speak to them “as a friend”. The men initially refused and insisted Smyth and his party leave the barracks or there would be bloodshed. The men agreed to hear out General Tudor only after Flanagan pleaded.

General Tudor came out to talk to the men dressed not in his full uniform as before, but in a civilian tweed suit. He said: “Well men, I would like to say just a few words to you as a friend. Just to show you I am a friend, I will shake hands with each one of you”, which he then did. He continued: “Although I am an Englishman and was born in Kent, my ancestors came from Ireland. I like Irishmen.” He then advised them that Dominion Home Rule would be applied for all Ireland, and for their service, twelve years would be added for pension purposes. Constable Byrne responded: “We have heard all these kind of promises in the past and we know that it ends up in nothing. If you are serious about those promises, why are you leaving our men in police huts where they can be shot like rats?” General Tudor asked how many huts were in the district. Byrne replied “There are six huts in this district.” Tudor promised: “Consider these huts broken up from this date”. At this, Mee then commanded “Dismiss!”, then the men left the dayroom singing “A Nation Once Again” and “Wrap The Green Flag ‘Round Me”. When they returned after a few minutes, they saw that Tudor and Smyth and their party had left.

Mee then went to Flanagan’s office, and told him that the men appreciated his support, but they didn’t want him to ruin his career by taking their side. Flanagan, who came from Elphin, Co. Roscommon, replied: “When I look out there and see those fine lads who have shown so much courage and bravery within the past few days, I feel that I am the happiest man in Ireland. It has been a great privilege and honour to me to have been placed in charge of such men, and I would be unfit to live as an Irishman, were I to desert them. That I shall never do and God bless you all.”

According to Jeremiah Mee, he immediately wrote down Smyth’s speech word for word while it was still fresh in his memory. He signed it, along with Constables Thomas Hughes, John Donovan, and Michael Fitzgerald to corroborate its accuracy. The rest of the constables were not told about publishing the speech, in case the information would leak; the men feared the publication could be stopped and for their safety if that happened.

There are different accounts as to how the speech eventually made its way to the Freeman’s Journal to be published, as follows:

JEREMIAH MEE’S WITNESS STATEMENT

In the meantime I went up to the bedroom, which was the only private room in the barracks, and I wrote out as near as I could, word for word, Colonel Smyth’s speech. This was signed by myself, Thomas Hughes, John Donovan and Michael Fitzgerald. Our intention was to send the statement to Republican Headquarters in Dublin and have it published so that we might give evidence while still serving in the police force. Although we had complete confidence in all the men, we considered it too risky, to discuss the publication of the document with the whole lot lest it might inadvertently leak out before publication. If that happened, the document would never get publicity and the consequences for all of us would be serious.

When the document was signed, we contacted the local curate, Rev. Fr. Charles O’Sullivan. We gave him the whole story, including the written statement, and asked him to forward it to the proper quarter, and that once the document was published all the other signatures would be forthcoming. Father O’Sullivan forwarded the document to Republican Headquarters, and it was returned for the signatures of all the men. We explained to Fr. O’Sullivan, and he quite understood, the importance of having the document published without further delay and without any further signatures until after publication.

In this state of uncertainty we remained until the 6th July when five of us, Thomas Hughes, John Donovan, Michael Fitzgerald, Patrick Sheeran and myself left the force without either resigning or being dismissed. Four of us travelled to Limerick by train and received a great reception from the railway men at Limerick who somehow had got the word that we were the

Listowel mutineers and on our way home.

On 10th July the Smyth speech was published fully in the “Freeman’s Journal”, a daily newspaper published in Dublin.

JOHN MCNAMARA’S LETTERS

Mee, Hughes, Donovan & Fitzgerald went to the offices of the Freeman’s Journal, a daily newspaper printed in Dublin, and gave a full account of what had occurred in Listowel Barracks. Shortly thereafter a reporter visited the town to verify the story and to receive more signatures to the already signed statement of the five men. Constable John McNamara received word that James Crowley, V.S., who later that year became the Sinn Féin representative for North Kerry, wanted to see him in his office. There he met the Journal reporter who asked him to read the signed statement and if McNamara believed it to be the truth and the whole truth, to sign his name under the other five, which he promptly did. He was also asked to obtain the signatures of the other men present on the day of the Mutiny, and despite the difficulty and danger of securing these he returned the following afternoon with eight more signatures. Before leaving for Dublin the reporter left a copy of the document with the parish priest, Rev. Charles O’Sullivan. The full story appeared in the first edition of the Freeman’s Journal on July 10th, however it was soon suppressed, and the editor and owner arrested as a result.

FR. ANTHONY GAUGHAN IN ‘LISTOWEL & ITS VICINITY’

At this stage there was a very important development. John McNamara went to James Crowley, V.S., who later that year became the Sinn Féin representative for North Kerry, and gave him a detailed account of what had happened, and a statement signed by the fourteen constables who resigned, describing the remarks of Colonel Smyth and requesting an official investigation into the incident. Crowley had the entire story printed by Robert I. (Bob) Cuthbertson and motored to Dublin with it that afternoon, and the full story appeared in the Freeman’s Journal the following morning. However, it was seen in good time by the authorities and was supressed. Subsequently it appeared in the Freeman’s Journal of 10th July, 1920.

To see the Freeman’s Journal article click here

The other constables immediately phoned the other main RIC stations for Kerry in Killarney, Tralee, Castleisland, Kenmare, and Dingle; the other stops on the military officials’ tour. They found the constables in these other stations sympathetic. Smyth found the police in Tralee hostile and was met by shouts of “Up Listowel!” among the constables in Killarney. They cancelled their tour and returned to Dublin Castle.

Fallout

Following the publication of Smyth’s speech in the Freeman’s Journal, Mee and Donovan met with members of the Dáil Cabinet: Michael Collins, Erskine Childers, and the Countess Markievicz to discuss the Mutiny. Childers had Smyth’s speech published in the Irish Bulletin, the official gazette of the provisional government of the Irish Republic.

On 14th July, the issue of Smyth’s speech was raised in The House Of Commons in Westminster by MP (Member of Parliament) for Liverpool, T.P. O’Connor; a native of Athone, Co. Westmeath. He said that Smyth’s remarks were calculated to cause serious bloodshed in Ireland. Sir Hamar Greenwood responded that Smyth had informed him that what he said was what had been debated in that House on 22nd May by the Attorney General for Ireland, Sir Denis Henry; and he did not exceed those instructions. Smyth was subsequently called to London to see Prime Minister Lloyd George. After two days in London, Smyth returned to Cork.

To read the full text of the House of Commons debate click here

Comparison was drawn at the time to the Amritsar Massacre in India on 13th April 1919 when British troops opened fire on civilians killing at least 379 people.

On 17th July 1920, in Cork, Smyth was assassinated by a six-man team from the Cork No. 1 Brigade of the IRA; led by Dan “Sandow” O’Donovan. The information was supplied by Seán Culhane, from Glin Co. Limerick, a Brigade member who was also one of the gunmen. One Account states that Smyth was told: “Colonel, were not your orders to shoot on sight? Well you are in sight now, so prepare!” before he was shot, but Culhane’s witness statement said there were no “preliminaries”.

To read Sean Culhane’s witness statement to the Bureau of Military History click here

Smyth’s funeral was held in Banbridge, Co. Down and was followed by sectarian riots for three days. Loyalist anger was exacerbated by the refusal of some railway workers to handle his body en-route to Ulster. Catholic homes were burnt in Banbridge, and nearby Dromore, Co. Tyrone.

Also in July, District Inspector Flanagan was suspended and eventually dismissed from the RIC with a very modest pension. There were mass resignations in the RIC of some 1,100 men within three months. The departing constables were replaced with an increased presence of Black and Tans, also nicknamed “Tudor’s Toughs”, after General Tudor. Also, the feared Auxiliary Division of The RIC, (ADRIC) known as “Auxies”; recruited from former British Army officers.

Smyth’s brother, Major George Osbert Sterling Smyth became a member of The Cairo Gang; secret British Intelligence agents working against the IRA, to avenge his brother’s death. He was transferred from Alexandria, Egypt at his insistence. He was shot and killed on 12th October 1920 in Drumcondra, Dublin by Dan Breen and Seán Treacy, whom he was trying to arrest. Treacy, who had initiated hostilities with Dan Breen at Soloheadbeg, was himself shot and killed in Talbot Street in Dublin two days later.

The crucial influence and importance of the Listowel Mutiny is now generally agreed by historians. The mutiny by members of the RIC in the police barracks in Listowel in June 1920 was one of the most significant events in Ireland’s War of Independence. As news of this spread throughout the RIC and later appeared in the press, the pace of members of the force taking early retirement or being dismissed quickened. Eventually, by 1st March 1921, 2570 members had left the force. Their places were taken by the hastily-recruited Black and Tans. For the most part, these were ex-soldiers and they received little, if any, serious police training. Their indiscipline and the outrages for which they were responsible alienated the Irish people, most of whom had no enthusiasm whatsoever for the policy and actions of Sinn Féin and the IRA. The result was that the crown forces found themselves operating in an increasingly hostile environment which cast serious doubts on their capacity to successfully pacify the country.

The Listowel Mutineers

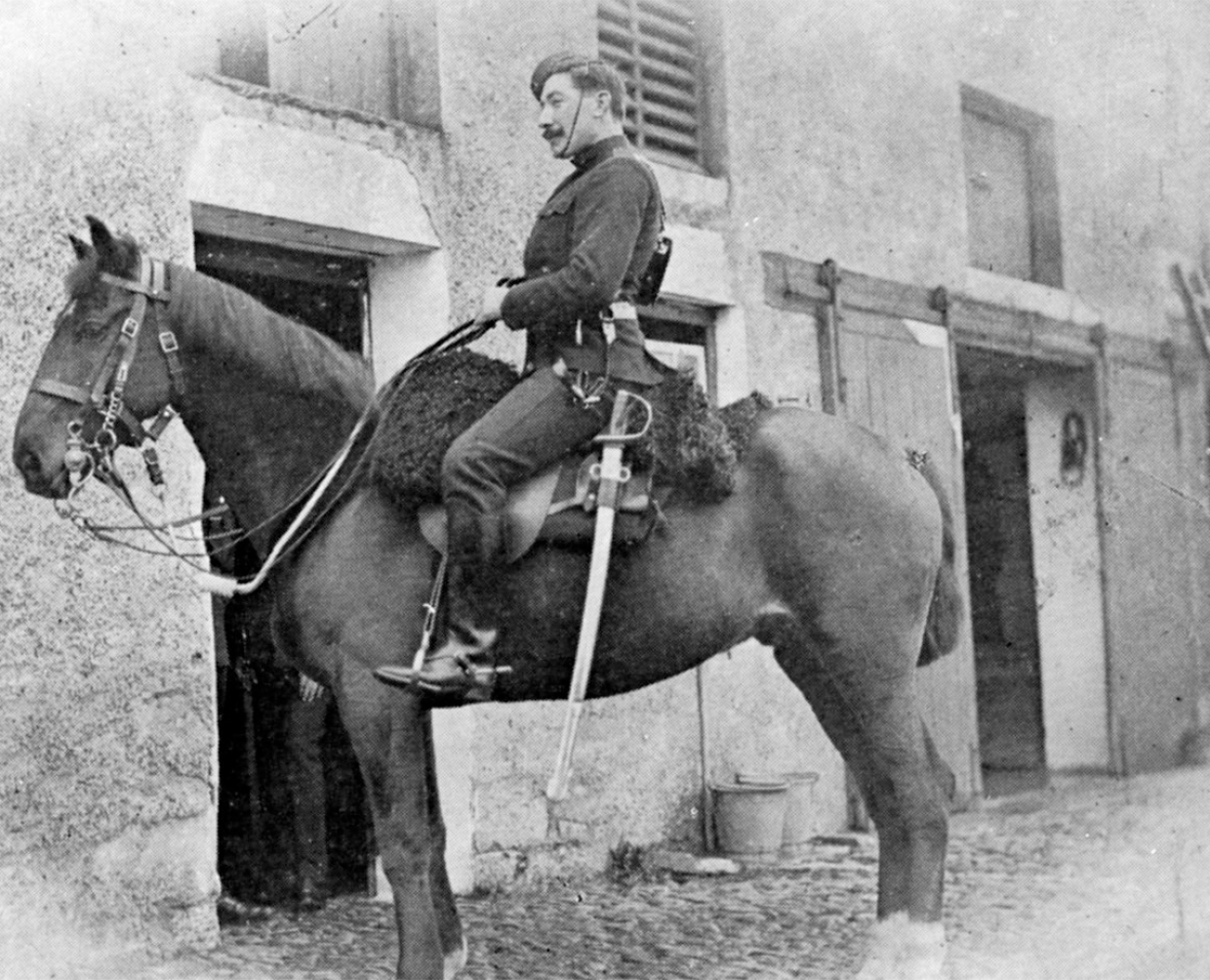

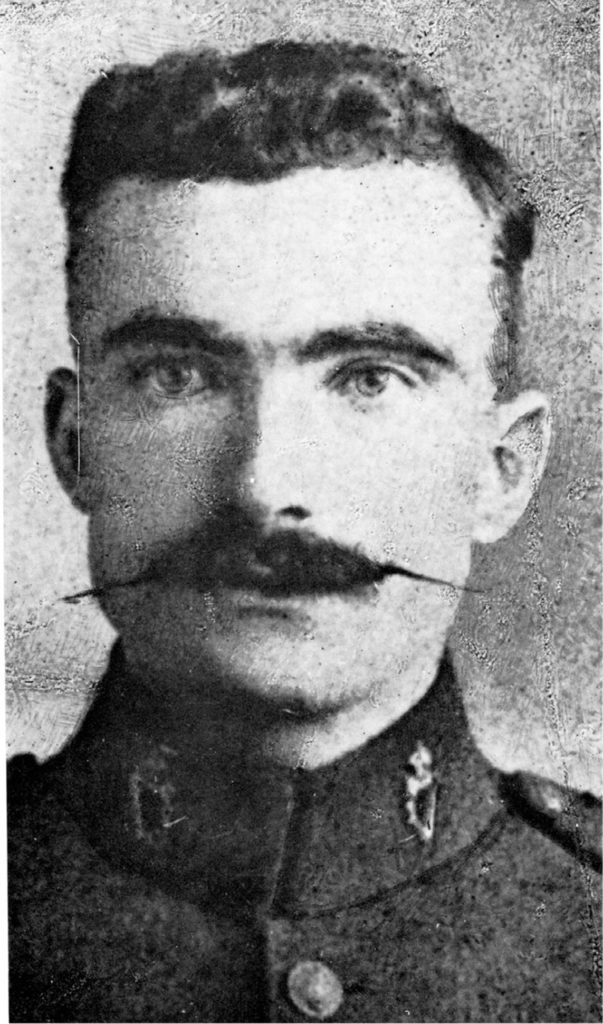

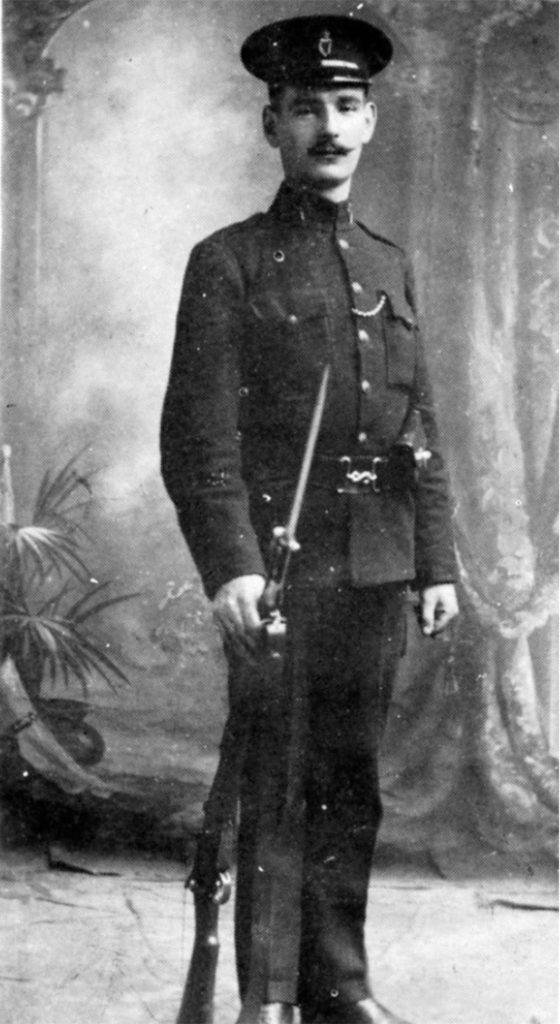

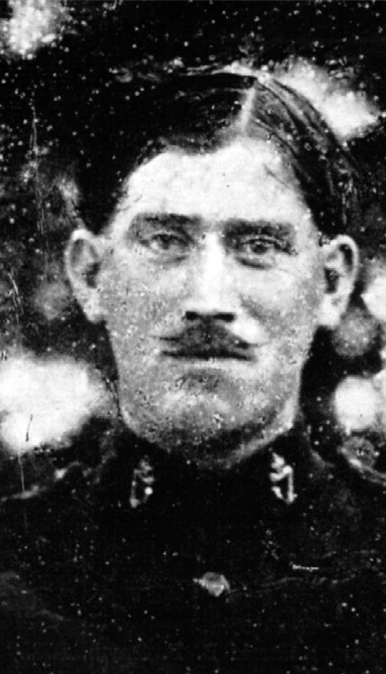

Constable Jeremiah Mee

My father, Jeremiah (‘Jerry’) Mee, was born in the townland of Knockanes, just outside Glenamaddy, Co. Galway on 29th March 1889. He was the 4th child of my grandparents, John and Ellen, who together had 9 children – 4 girls and 5 boys.

The Mee children grew up together on the 20 acre subsistence family holding – often living in and out of adjacent relatives’ and neighbours’ homes at harvest times. They attended the nearby Stonetown National School until the age of 12 after which they were required to pick up whatever work was available locally or on the farm. Like so many Irish families of the period, emigration devastated the Mees. Three sons – John, Dan and Michael – found themselves forced to abandon Ireland during the early 1900s in order to seek out better opportunities in America. It was an enduring and traumatic break up which Dad, his four sisters (Kate, Margaret, Norah and Ellen) and younger brother (Luke) never forgot.

In later years Dad and, subsequently, Uncle Luke, were lucky enough to find jobs in the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC). Dad joined in 1910 and, although he never came back to live in Glenamaddy thereafter, the village and locality always remained, for him, a personal haven. He regularly brought Mum and us, as children, down to stay. This allowed us to spend many happy days with Grandpa, Granny and other family and friends.

At heart, Dad was a private man who was always reluctant to speak or write publicly either about immediate family or his relationships with close friends of whom there were many. Above all, he hated ostentation. His reticence both disguised and signified a deep love for ‘ordinary’ people, especially those from farm communities and disadvantaged neighbourhoods in Ireland. This love also explains why, during his years in the RIC, he became active – alongside other young officers like his friend Thomas McElligott – in an ultimately unsuccessful campaign to both gain recognition for a police union and transform the Constabulary into a more publicly acceptable civic police service.

After these efforts failed, Dad left the RIC in 1920 eventually taking up a position in the Ministry of Labour in the First Dáil under the leadership of Countess Markievicz. In addition, he became part of Michael Collins’ network of underground agents. He was amongst those who helped ‘the Big Fella’ expand his extensive communication channels with secret contacts inside the police as well as amongst supporter organisations in Belfast, Derry and England. At the Ministry of Labour under Countess Markievicz, Dad’s main function was to encourage and facilitate members of the RIC and the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) into either leaving the force or else agreeing to act as informants and saboteurs against the British government administration in Ireland.

Dad married my mother, Annie O’Rourke, on 16th August 1920. He and Mum had met, a few years earlier, whilst he was still in the RIC and stationed at Ballintogher in County Sligo. Mum was from nearby Dromahair in County Leitrim. Like Dad, she was from a farming family. She was also a great lover of songs, humour, the outdoors and her garden. Her instinctive free spiritedness seemed to help Dad balance out his natural penchant for orderliness, discipline and hard work.

Perhaps because of the trauma of family separation caused by emigration and having had to leave school so young, Dad remained a tireless self-improver all his life through physical fitness, reading, writing and as a husband and father. Following the pain of the Civil War, and a period of unsatisfying work as an oil depot supervisor in Sligo, Dad – with Mum’s support – obtained an appointment in 1932 as an employment insurance inspector for Counties Westmeath and Longford at the Department of Local Government and Public Health. As well as his own abilities, he was aided in his application by his past record of work both for the First Dáil and his much loved Irish White Cross.

By 1935, Mum and Dad had 6 children – Eileen, Kathleen, John, Peggy, myself and Joe. Both Mum and Dad were determined that we all should have a chance at gaining a solid academic education if possible. They saw education as the best way to help their children – especially the girls – broaden their choices and opportunities in life. In this they succeeded. Each of us attained 3rd level or training qualifications and all were, thanks to our parents, able to pursue professional careers and vocations of our choosing.

Sadly, Mum died suddenly and unexpectedly in 1948 at the age of just 52 and shortly after the family had moved to Dublin. Dad was devastated by her loss and never fully recovered from it, coming as it did in the same decade as the death of his father, mother and beloved sister, Norah, who was only 34. He continued, though, to work as an employment insurance inspector. It was around this time that he began writing his memoirs and started lobbying various Irish governments to provide many former RIC colleagues with proper pensions.

Dad lived long enough to see his eldest child, Eileen, married in 1952. He was also, in equal measure, delighted and saddened as his children gradually moved away to pursue jobs and training. But Mum’s loss always weighed heavily on him. Following a short illness, Dad died in Sir Patrick Dun’s Hospital on Grand Canal Street in Dublin on 8th May 1953. He and Mum are buried together in Glasnevin Cemetery alongside my wonderful sister, Kathleen, who passed away in 2010. I always remember Dad as both a strong individual and a very loving, tender father.

Dad, in his will, gifted all his original papers and memoirs to my dear, late sister Mrs Peggy Cook (nee Mee). These were donated by the family, in their entirety, to the Garda Museum in Dublin Castle in 2013.

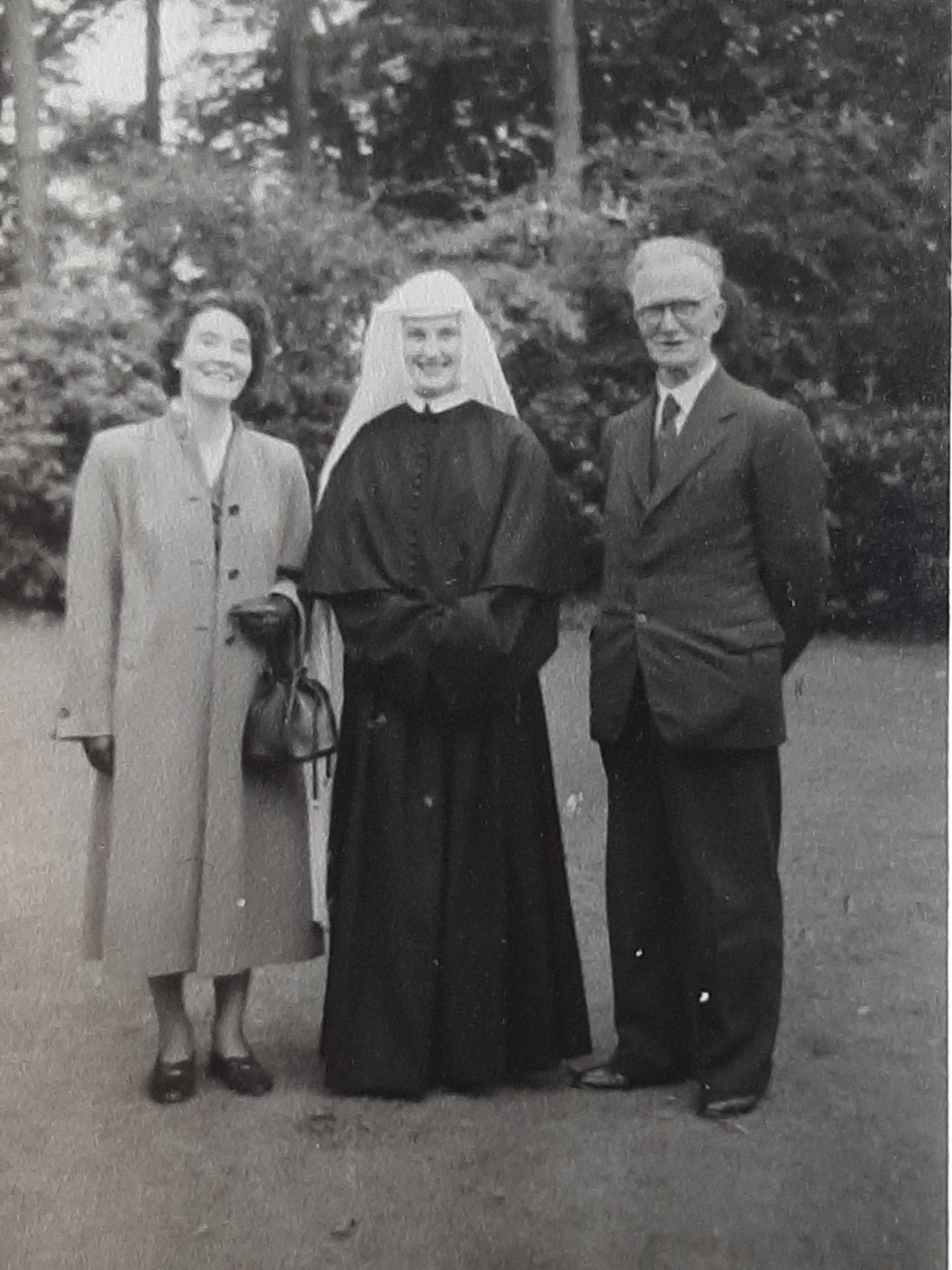

SISTER TERESA MEE

Holy Child Convent, Harrogate, England.

Here the audio of John Drummy voicing Jeremiah Mee’s account

John Drummy Voicing Jeremiah Mee’s Account

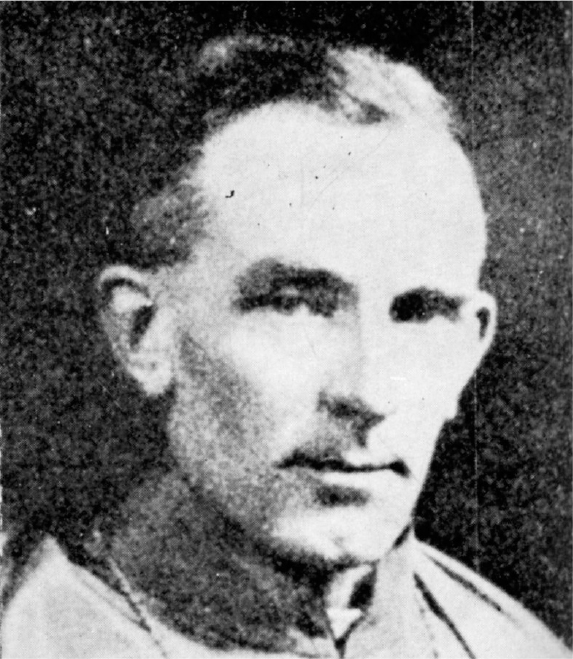

Audio PlayerConstable Thomas Hughes

Thomas Hughes was born in Hollymount, Co Mayo on 1st February 1891 to Peter, a shopkeeper, and Mary nee Canny. He studied at Ballinrobe C.B.S. between 1906 and 1910, after which he became a member of the Royal Irish Constabulary. He left the force in circumstances which are well known and have been the subject of a book and several articles. He was one of the constables who took part in the famous ‘Listowel mutiny’ of 1920, when a group of policemen, led by Constable Mee, refused to obey the order to shoot on sight during the war of independence. When the order was given Thomas was one of those who went into the day room, removed their belts and threw them on the table.

Thomas was a ‘late vocation’ to the Society of African Missions (SMA) at 31 years of age. On joining the Society he studied at the Sacred Heart College, Ballinafad, Co Mayo (1920-192l) before joining the novitiate and house of philosophy at Kilcolgan, Co Galway (1921-23). Thomas was admitted to permanent membership of the Society on 15th July 1923. He spent three years at St. Joseph’s theological seminary, Blackrock Road, Cork (1923 1926), and completed his theological formation at Dromantine, Co Down, to where the seminary was transferred in September 1926. He was ordained a priest by Bishop Edward Mulhern of Dromore diocese, at St. Colman’s cathedral, Newry, on 16 June 1927. He was one of a group of eleven ordained on that day.

After ordination Thomas was appointed to the vicariate of the Bight of Benin, a vast jurisdiction in south western Nigeria. On his arrival, in October 1927, Ferdinand Terrien, the vicar apostolic, appointed him to the founding staff of St. Gregory’s college, Ikoyi, Lagos, Nigeria’s first Catholic secondary school, which opened its doors in January 1928. Fittingly, Leo Hale Taylor, founding principal of St. Gregory’s, placed Thomas in charge of discipline. Thomas also looked after the school’s finances. During the two years he spent at St. Gregory’s he won a reputation for fair mindedness and firmness. In September 1929 Thomas became superior of Holy Cross mission, Lagos, serving there for a year. Between 1930 1933 he was superior of Ijebu Ode mission. Thomas impressed himself on his superiors and colleagues as a natural leader. This was formally recognised in 1932 when his Irish superiors appointed him ‘visitor’, or superior of his Irish confrères, responsible for their spiritual and temporal welfare.

On 12th January 1934 Thomas was nominated prefect apostolic of the prefecture of Northern Nigeria. This vast jurisdiction covered an area of over l00,000 square miles between the Sahara and the Niger. Three months after his appointment this territory was divided into the prefectures of Kaduna and Jos, and Thomas was assigned to the former jurisdiction. The Kaduna prefecture at that time had a mere four residential stations, but within as many years Thomas had founded four more. ‘

On 12th January 1943 Thomas was appointed vicar apostolic of Ondo Ilorin with the title bishop of Nepte. His ordination as bishop took place at Holy Cross, Lagos, on 9th May 1943. When the Nigerian hierarchy was formally erected in 1950 Thomas became the first bishop of Ondo diocese. He remained in charge of Ondo diocese until the time of his death.

Thomas had a great interest in sport and, while busy with the affairs of his diocese, kept up to date on the All Ireland championships, and especially the fortunes of Mayo. A sociable man, he liked to see visitors arriving in Akure, his headquarters, especially if they could play ‘solo’. He was a very good player, having learned perhaps in the police stations of the R.I.C. Thomas began to experience cardiac problems from 1955 and was frequently hospitalised. He had already submitted his resignation from Ondo when he died in Cork on 17 April 1957, aged 66 years.

Constable Loughlin Dolan

Loughlin Dolan was one of a large family of nine brothers and two sisters. He was born in the 7th July 1889 in Lusmagh Co. Offaly to a farming family. His father was also Loughlin and mother Margaret nee Melody. His parents had died by the time he was 18. They struggled to make ends meet and on 15th Oct 1913 aged 24, he enlisted in the RIC, and was stationed in Listowel barracks.

His RIC record states he was moved to Cavan after the Listowel mutiny but his family said he never went there. He was officially dismissed on the 20th of Nov 1920. He moved to Liverpool after the mutiny and in January 1922 he arrived in Australia. Fearing for his life and convinced that he was still being pursued by the authorities, he went into hiding in the Australian bush near Adelaide.

For 3 years he lived in isolation, trapping rabbits for food. By 1925, he was suffering from starvation and emerged from the bush at Strathalbyn. His physical appearance caused quite a stir and he appeared on the front page of the Adelaide Mail in 1925.

He became known as ‘ the hermit of the hills ‘ where they described him as handsome, genial and cultured, but they also say ‘ from a distance his tall , gaunt , limping, bewhiskered face, tight ill-fitting garments and long hair give the appearance of extreme age. He had a look of startled fear’.

He was hospitalized for 6 months in a hostel for homeless men to recuperate. During this time he wrote to his sister my grandmother. In his letter he says:

‘I don’t like this country…I don’t like to be alone in this world… this is a very wild country. Ye might see me in Cork city, like when I get tired roving through this world, I may return when old age catches me’

This was his only letter home.

His brother Ned who was also in Australia and tried many times to find him wrote home in 1952 and stated that a secret service agent acting on behalf of Canada House London came looking for Loughlin. He said he would return when he had news but never did.

On line records have two entries for Loughlin. In 1933 he was arrested for Vagrancy in South Grafton 600kms north of Sydney.

The last record of him is on a register of electors in 1943, in Nymboida, a small rural town near Grafton, he would have been aged 54.

There is no record of his death.

Constable John P. McNamara

John McNamara was born in Crusheen, County Clare on 8th of May 1899. He joined the RIC on 1st November 1918, one month before the general election and two months before the first shots were fired in the War of Independence. He was appointed to Listowel on 1st June 1919.

During his entire time at Listowel he refused to carry a gun outside of the barracks, even a revolver for his own protection, and, for weeks before the mutiny, he refused to do any military work or to co-operate with the military in any way. Three other RIC men joined him in his refusal to work with the military and one also refused to carry a gun outside of the barracks.

He took part in the Listowel Mutiny on 19th June 1920, refusing to follow orders that would be considered war crimes by today’s standards. Immediately after the mutiny he and many others resigned but the RIC refused to accept their resignations. Four of the mutineers walked out of the force. Most of the remaining mutineers were transferred to other stations. John McNamara was one of just four of the mutineers who remained in Listowel.

At this point, the leader of the mutiny, Jerimiah Mee, was now working for the senior leadership of Sinn Fein in Dublin. He asked Michael Collins what the four mutineers who remained in Listowel should do. Collins advised that they should remain in the force, try to form an ‘underground’ and make available as much information as possible about the security forces. They were also assured that after the hostilities ceased, they would not suffer financially or otherwise for remaining in the RIC.

McNamara and his colleagues agreed and a permanent line of communication was established. The local IRA was under instructions from Michael Collins to leave them alone and to provide them with any assistance they required. Week after week, they sent valuable information regarding the movement of troops and confidential instructions to the force, all of which were first passed to the local IRA in Kerry, before being transported to Dublin and ultimately into the hands of Michael Collins.

The RIC knew they had a leak. A local officer in the IRA had been arrested and the police found confidential police documents in his possession that had been supplied to him by John McNamara. If McNamara had been caught, it would have meant immediate death for him.

After the mutiny, whenever policemen were required from the barracks for duty outside the Listowel police district John McNamara and Michael Kelly were always selected.

McNamara and Kelly were assigned to Cork city on 17th July. On arrival, the head constable told them not to reveal their involvement in the mutiny to anyone, telling him the Black and Tans had to be restrained from travelling to Listowel to burn down the police barracks when they heard of the mutiny. Later that day, McNamara and Kelly went missing from duty with the RIC. On the same day, the man who made the speech that caused the mutiny, Divisional Commissioner Smyth, was assassinated in the city.

The Head Constable in Cork, fearing for their safety, placed McNamara and Kelly in his office which he instructed them to lock from the inside and not to open the door to anybody but him. They spent the night there while another RIC constable was searching the city for them.

They returned to Listowel safely. Every night they refused to join the Black and Tans patrol of the area, insisting they would only patrol with regular police. Their refusal to carry weapons outside of the barracks meant they were withdrawn from patrol altogether.

They were frequently sent to Limerick Junction train station, ordered to board outgoing trains and look for anything suspicious. They refused to board any of the trains.

Eventually, they were court martialled.

Although John McNamara and Michael Kelly had been supplying intelligence directly to the Kerry IRA and ultimately to Michael Collins for months, the only charges that the British could bring against them was gross insubordination and conduct unbecoming an officer. On these charges they were brought before a disciplinary court on dismissed from the RIC on 1st November 1920.

However, their luck was running out. The net was closing in on them.

On returning to collect personal items from Listowel after his dismissal, McNamara learnt that he and Kelly were now hunted men, wanted by the Black and Tans. A friendly RIC Constable warned him to get out of town fast because the Black and Tans were now aware that he and Kelly were in Cork city on the night that Smyth was shot and that they went missing from their detail on that day. They believed that McNamara and Kelly identified Smyth to the Cork IRA. McNamara and Kelly contacted an IRA source to verify the information. He confirmed that the Black and Tans were overheard saying they could bring them in dead or alive.

The local IRA provided the pair with refuge and arranged their escape to Dublin. In Dublin, they were continuously on the run. They moved from place to place to avoid detection while two of their former comrades from Listowel searched the city for them.

Collins requested that McNamara and Kelly travel to the US to give evidence about the black and tans to the American Commission of Inquiry into Conditions in Ireland.

They left in January 1921, travelling with a sealed handwritten letter from Michael Collins to Harry Boland in a secret compartment of their luggage. All of their travelling expenses were paid for by the first Dail.

On arrival they were met by a delegation led by Harry Boland who paid a glowing tribute to them before McNamara and Kelly were lifted off their feet by a jubilant crowd and carried shoulder high to a waiting car.

At the request of Harry Boland, they began a speaking tour of Connecticut to raise awareness and funds for an organisation called the American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic. They attracted huge crowds. Often the halls were so packed that they had to enter through the fire escapes. Thousands of dollars were raised through their efforts. The membership of the American Association for Recognition of the Irish Republic increased by thousands and they found it difficult to find a hall large enough to accommodate the crowds who wanted to attend their meetings.

They were officially received by the mayors of all the large cities in Connecticut.

Seeing their success, Harry Boland regretted that the IRA didn’t infiltrate police barracks throughout Ireland saying that it would have meant that overnight, every police barracks would be in the hands of the IRA with little or no bloodshed.

Both men signed affidavits for the American Commission of Inquiry into Conditions in Ireland

John McNamara reported that:

- On arrival in Listowel the Black and Tans fired shots at men, women and children from their lorries.

- They starved and tortured prisoners who were ultimately never even charged.

- They murdered a postman, a blacksmith and a 70 year old pensioner.

- They sprinkled gasoline on the clothing of four suspected Republicans and set fire to them, burning them to death.

- They boasted that they had shot and killed a former member of the R. I. C. who had resigned and made this boast as a threat to the members of the R. I. C. at Listowel to keep them in line.

- They baton charged a congregation as they left mass

- They burnt down a public house and shot suspects dead in the middle of the night.

- They broke into public houses and confiscated the liquor for their consumption.

- They stole food, fowl and other farm animals at night on raids which they conducted dressed in civilian clothes and with blackened faces.

- None of the officials in charge of the barracks reprimand them for any of their actions.

His affidavit, along with Kelly’s, are included in the American Commission of Inquiry into Conditions in Ireland. The chairman of the commission devoted two pages of his summary to their evidence. He closes his summary stating “They are the circumstantial evidence which proves that Divisional Commissioner Smyth outlined to the policemen of Listowel barracks the official policy of the British Government in Ireland”.

After the Treaty was signed the hero’s welcome disappeared. McNamara and Kelly were left destitute, sleeping on park benches in Central Park and washing dishes to earn money food. They eventually began to find their feet, first securing work on the rail network where John McNamara went on to become an inspector. In 1928, he joined the New York Police Department where he remained for the rest of his career.

The Free State Government set up two committees to compensate members of the RIC who resigned or were dismissed because of their nationalist views. Both committees refused to award a pension to John McNamara because of his short service with the RIC. He was furious with this, noting that had he followed the orders of the Black and Tans he would have qualified for a generous pension on disbandment of the force. He also had written assurances from Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith that he wouldn’t suffer financially for supporting the independence struggle.

The second committee recommended providing him a job in the Guards which would have enabled him to return to Ireland. This recommendation went to De Valera’s cabinet in 1936 but they refused to offer him the position. He never returned to Ireland.

He died in 1969 and is buried in New York.

From the letters of John McNamara 1949/50

To read John McNamara’s letters to Maurice O’Sullivan, Listowel, click here

Constable Michael Kelly

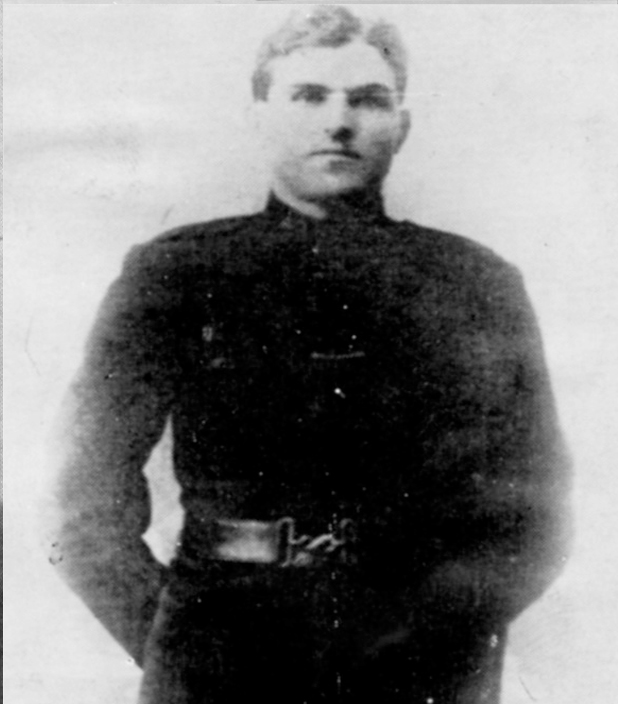

Michael Kelly was born in Ballycastle, Co. Mayo in 1895. He enlisted as a member of the Royal Irish Constabulary at Ballycastle in October, 1914. After six months training at the RIC depot at Phoenix Park, Dublin, Kelly was appointed to Glenbeigh police barracks, Co. Kerry, and was stationed there from April, 1915 to July, 1917. From July, 1917, to May, 1918 he was stationed at Lisselton, Co. Kerry. From May, 1918 to January, 1919 he was stationed at Ballybunion and from January, 1919 to November, 1919 he was stationed at Ballylongford. From November, 1919, to April, 1920, he was stationed again at Lisselton and from April, 1920, to September 26, 1920 he was stationed at Listowel during which time he participated in the Listowel RIC Mutiny.

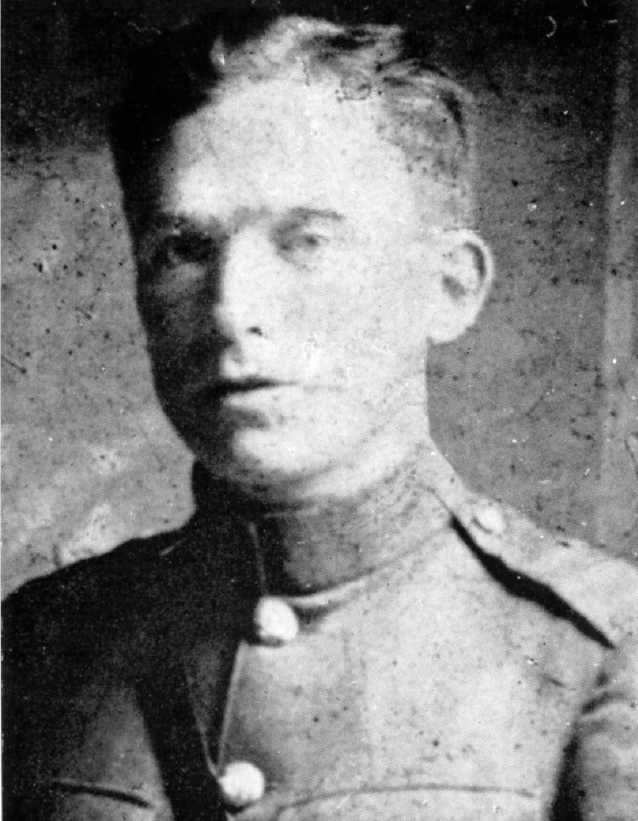

Constable Michael Fitzgerald

Michael FitzGerald was born in September 1898 at Castlegar, Ahascragh, Ballinasloe, Co. Galway. James, his father, died in 1905 leaving his widow Kate Carroll with a family of 7 to raise. Fitzgerald joined the British Army in September 1915 and saw active service with the Connaught Rangers from 1916 to 1918. He was demobilised in December 1918 and returned home. In August 1919 he joined the RIC, and in December that year, after his training at the depot, he was appointed to Listowel police barracks. From July 1920 until the Truce he threw in his lot with the IRA unit in South Roscommon. During the Civil War he fought on the Free State side reaching the rank of captain. He was demobilised in March 1924 and worked as a clerk in the Employment Exchange, Ballinasloe from 1925 until June 1926 when he joined the Garda Síochána. He died on 8th December, 1945 aged 47 years.

Constable Francis Byrnes

Francis Byrnes was born in Tulla, Co. Clare in 1886. His father John was born in Co. Limerick and was also an RIC constable. The 1901 Census of Population lists Francis as a scholar, aged 16 years. He joined the RIC in 1907 and served in Listowel from1908 to 1920 and Camlough, Co. Armagh from 1920 to 1921.

He died in Tulla on the 23rd January 1965 and his Death Certificate lists his son John as informant and being present at death. His occupation is recorded as RIC Pensioner.

Constable John Donovan

John Donovan was born at Clarina, Co. Limerick in 1891. He joined the RIC on 15th Sepember 1913. Having completed his training at the depot he served at Skreen (1914-15), Kesh (1915-16), Mullaghroe (1916-17), Ballymote (1917-19) and Listowel (1919-20). Following the Listowel Mutiny Countess Markievicz succeeded in placing Donovan in employment as Manager of the Court Laundry, Harcourt Street. He died on 19th May 1964.

Constable Patrick Sheeran

Patrick J. (Packy) Sheeran was born at Straide, Co. Mayo on 16th March 1892. He joined the RIC on 16th March 1912, and having completed his training he served at Glenbeigh (1912-14), Killorglin (1914-17) and Listowel (1917-20). When stationed in Listowel in early 1920 he married Margaret Morrissey of Brosna. He was on leave and in Brosna with his wife when the mutiny occurred. When he returned from leave, however, he associated himself with his comrades, and a few weeks later left the barracks. He died on 16th April 1966.

To view film recording of Dr. Padraig Sheeran, grandson of Patrick Sheeran watch below

Constable Andrew Robinson (Kerry)

To listen to a audio recording of Joe Robinson, a grandson of Constable Andrew Robinson listen below

Audio of Joe Robinson, a grandson of Constable Andrew Robinson

Audio Player

Constable John Sinnott (Kilkenny)

To view film recording of Ann Waldron, daughter of John Sinnott watch below

Constable Thomas R. Reidy (Clare)

Constable Patrick O’Neill (Wicklow)

Constable Joseph Downey (Kildare)

Constable Patrick Regan (Mayo)

The Listowel Police Mutiny 1920

View the full film of all the videos from this exhibition – watch below

Acknowledgements, Sources & References

Acknowledgements

Kerry Writers’ Museum wishes to acknowledge the following for their contribution to this exhibition:

- Jimmy Deenihan and Cara Trant, Exhibition organisers

- Fr. J. Anthony Gaughan

- Donal J. O’Sullivan, retired Garda Superintendent

- Kevin Rooney

- Tom Dillon, historian, Listowel

- Teresa & Ciarán Mee, daughter & grandson of Jeremiah Mee, Belfast & UK

- Naoive Coggin, grandniece of Loughlin Dolan, Co. Waterford

- Padraig Sheeran, grandson and the family of Patrick Sheeran, Brosna & Kildare

- Ann Waldren, daughter of John Sinnott

- Luke Mee & Glenamaddy/Boyounagh Heritage Project

- The Garda Museum & Historical Society, Dublin

- Mary Feehan, Mercier Press, Cork

- Martin Curly, Listowel RIC Mutiny 1920 Facebook page administrator

- Muiris Crowley, actor, Killorglin

- Vincent Carmody, Listowel

- Mary Cogan, Listowel Connection

- James Pembroke Film Productions

- Charles Nolan Film Productions

Historical Sources

Published Sources

Memoirs of Constable Jeremiah Mee RIC – Rev. Fr. J. Anthony Gaughan (Mercier Press 1975)

The Irish Constabularies: 1822-1922: A century of policing in Ireland – Donal J. O’Sullivan (1999)

Listowel and its Vicinity, Rev. Fr. J. Anthony Gaughan (Mercier Press, Cork 1973)

Online Sources

Bureau of Military History Archive

UK Parliament Archives

Listowel Connection Blog

Irish History 1916 through to 1923 Facebook Page – Article by Kevin Rooney

Further References

Fergal Keane interview with Sean O’Rourke about his book Wounds – A Memoir of Love & War, which includes information about the Listowel of 1920.

Recalls incidents involving his Cumann na mBan grandmother Hannah Purtill in Listowel, who was also mother to John B Keane.

Fergal Keane interview with the Belfast Telegraph: